Gradable adjectives can only be used with grading adverbs:

a bit, dreadfully, extremely, hugely, immensely, intensely, rather, reasonably, slightly, very

That’s a bit expensive, don’t you think so?

It was extremely frightening to see her jump off the cliff.

These designs are reasonably good.

Non-gradable adjectives can only be used with non-grading adverbs:

absolutely, completely, entirely, perfectly, practically, simply, totally, utterly, virtually, almost, exclusively, fully, largely, mainly, nearly, primarily

The room was entirely spotless, no one would have thought that a murder had been committed there a few hours before.

I find his ideas completely ridiculous.

The person primarily responsible for this decision is the chief executive.

Non-gradable adverbs which indicate the extent of the quality, such as almost, exclusively, etc., are commonly used with classifying adjectives:

The experiment was carried out for exclusively scientific purposes.

Sometimes gradable adjectives can be used with non-grading adverbs, and non-gradable adjectives with grading adverbs either to give special emphasis or to be humorous:

NB! Not all the adverbs can go with all the adjectives given in each of the tables above. For instance, we can say “absolutely huge”, but we wouldn’t usually say “completely huge” unless it was for a particular emphasis or humour.

- I found a $10 bill on the sidewalk this morning. - You’re virtually rich now! (non-grading adverb + gradable adjective)

Some more examples of adverb + adjectives that don’t normally collocate: perfectly different, mainly wrong, fully unlikely

The adverbs “faily”, “really”, “quite” and “pretty” are commonly used with both gradable and non-gradable adjectives. The adverb “pretty” is rather informal.

Who could have known that she was really popular at school?

I’m pretty busy now, can we talk later?

This task is fairly impossible.

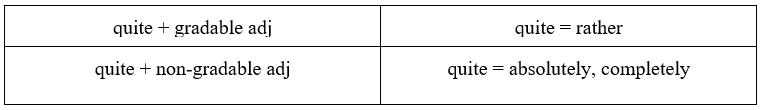

The adverb “quite” changes its meaning depending on the type of the adjective used with it:

She’s quite shy, isn’t she? (= rather shy)

My dad was quite furious when he saw that I had scratched his car. (= absolutely furious)

Yet we don’t use “fairly” or “very” with the following gradable adjectives which indicate that something is very good or necessary: essential, perfect, superb, invaluable, wonderful, tremendous.

Daily practice is really / pretty essential for those who learn foreign languages. (not “fairly essential)

* However, there are some exceptions to the rule:

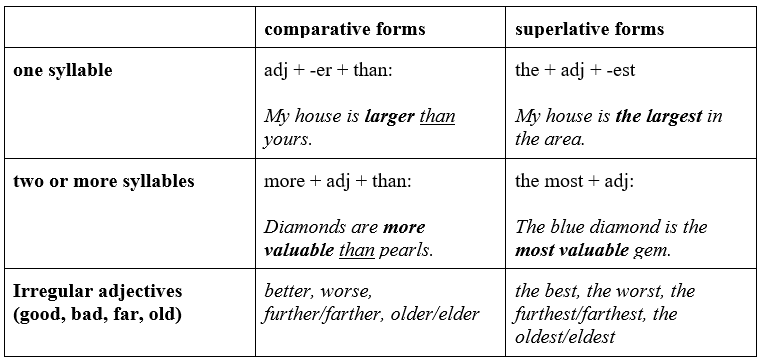

1) Participial adjectives (the ones ending with -ed) form the comparative and superlative with more and most:

I am more bored of his stupid jokes rather than him as a person.

2) Some other adjectives that form the comparative and superlative with more and most:

real, right, wrong, fun, afraid, alert, alike, alone, ashamed, aware, eager, certain, cautious, complex, direct, exact, formal, frequent, modern, recent, special

The party was more fun than I had expected it to be.

3) Two-syllable adjectives ending in -ly, -y, -ow, -r, and -l, as well as the adjectives common, handsome, polite, stupid, simple, mature, pleasant can have can have either more/most or -er/-est:

People here are definitely more friendly / friendlier than in my hometown.

4) When we add a negative prefix to two-syllable adjectives ending in -y, they can also take either more/most or -er/-est:

He is the unluckiest / the most unlucky man I’ve ever met.

5) We can sometimes use more as an alternative to the -er form to emphasise the comparison using the adjectives dark, cold, clear, deep, rough, fair, true, soft:

You think it’s cold here, but it’s definitely more cold in the attic. (or colder)

We sometimes omit the definite article before superlatives describing titles, awards, prizes, etc:

And the prize for most promising film-producer this year goes to Eleonor Smith!

Less and the least

We use less and the least as the opposite of more and the most. They are used with all adjectives, including one-syllable ones:

The new ad blitz proved to be less successful than the old one.

They were looking for the least experienced candidate.

(Not) as … as

We can say that two things are equal by using as + adjective + as:

This apartment is as expensive as the previous one.

To make the comparison more emphatic, we can add “just”:

Your academic achievements at university are just as important as your extracurricular activity.

To say that things are almost equal, we can use (just) about / almost / more or less / nearly + adjective + as:

My sister is nearly as old as me.

This movie is just as bad as the one we saw yesterday.

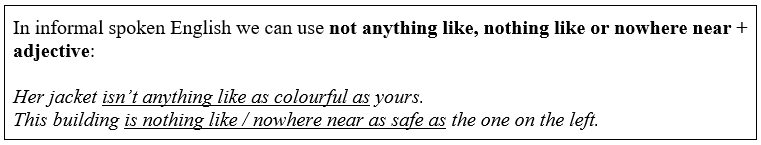

To make a negative comparison with not as / so + adjective + as:

I think my laptop is not as fast as yours.

This type of comparison can be modified with nearly or quite:

Healthcare in Spain isn’t nearly so expensive as in the US.

My grades aren’t quite as good as Jake’s.

No / not any + comparative adjective

We can use comparative adjectives to say that two things are equal:

to be + no + comparative adjective + than

The Oscars is no more prestigious than the Grammy. (= both of them are prestigious)

to be + not + any + comparative adjective + than

The Oscars isn’t any more prestigious than the Grammy. (= both of them are prestigious)

Progressive comparison

We can describe how something increases or decreases in intensity by repeating more or the same comparative adjective, with and between the repeated comparatives:

As the queue wasn’t moving at all, people grew more and more impatient.

Mark’s visits to his homeland became rarer and rarer.

Combined comparison

To describe how a change in one thing causes a change in another one, we can use two comparative forms with the. Note the use of the comma after the first clause.

The longer you stay silent, the worse the problem will get.

The verb “to be” can sometimes be omitted:

The crazier the idea, the more fun it is to try.

Contrastive comparison

When we contrast two related qualities, we always use more (not -er):

- Are you angry with me? - I’m more sad than angry.

He is more selfish than arrogant.

We can also use not so much … as or (rather) than:

I’m not so much angry as sad. He’s more selfish than arrogant.

Like and as

We often describe something by comparing it to something else which has similar qualities. These comparisons are known as similes:

as + adjective + as: Listening to his stories was as interesting as watching a thriller.

like + noun or verb phrase: The ship was like a skyscraper lying on its side.

NB! We use “like” before a noun to compare two things which only seem similar but in fact are different:

Although he looked like a shy young boy, he was actually a violent criminal.

NB! We use “as” before a noun when we are describing someone’s actual job, role, identity, or a function of something:

Sam is currently working as a housekeeper.

As and such

We can use as and not such to introduce a comparison with nouns. Here are the possible patterns:

as + adjective + a + noun + as:

I was looking for as undemanding a job as possible.

not as / not such + a + adjective + noun + as:

It wasn’t such a bad job as I’d expected.

We can use so, too and how followed by an adjective in a similar way:

It’s not so easy a process as it might seem at first.

- You’re a cheater! - A cheater is too strong a word.

Other cases

When most + adjective / adverb is used without the definite adjective, most becomes synonymous with “very”:

I tried to carry the box with the vase most carefully, but I broke it anyway.

We use as much / many as or as little / few as to say that a quantity or amount is larger or smaller than expected. Many and few are preferred before numbers; much and little are preferred with amounts (e.g. 15%, $50) and distances (5 metres):

Prices have plummeted by as much as 150%.

There weren’t many people in the club, possibly as few as twenty five.

We can use not + adjective / adverb + enough + to-infinitive to mean that there isn’t as much as is necessary to do something:

- Can you help me to get this box from the shelf? - I’m not tall enough to reach it.

We can also use “sufficiently” before adjectives to express a similar meaning to “enough”. This is preferred in more formal contexts:

Sadly, he didn’t play sufficiently well to qualify for the team.

We can use too + adjective / adverbs + to-infinitive to mean “more than necessary, possible, etc.” to do something:

She arrived too late to catch the last bus.

In rather formal English we can use too + adjective + a / an + noun:

I hope it wasn’t too silly an idea.

We can use so + adjective / adverb + that-clause to say that something existed or happened and then a specified result ensued:

It’s so simple that even a kid can do it.

He screamed so loudly that I rushed to the kitchen to see whether everything was alright.

Less often do we use so + adjective / adverb + as + to-infinitive with a similar meaning:

The difference was so subtle as to not be worth worrying about.

We can use go so / as far as + to-infinitive to talk about actions that are surprising or extreme:

No one could believe that he would go so far as to use force.